Survey: Coronavirus outbreak has the potential to threaten US economic growth

It was all quiet on the U.S. economic front at the start of 2020 — that’s until the coronavirus came along. Now, economists are scrambling to assess the impact from the deadly virus sweeping the globe.

Nearly 7 in 10 (69 percent) experts surveyed in Bankrate’s First-Quarter Economic Indicator poll said they expect a sizable economic impact from the coronavirus, which has infected more than 90,000 people worldwide.

The pathogen has cut off major companies, such as Apple and Toyota, from their global supply chains as quarantines leave factories shuttered. Meanwhile, restrictions have delayed millions from traveling to certain regions. These interferences are likely going to spill over to the rest of the economy, experts say.

“Disruptions to production are already occurring; manufacturers are facing shortages of parts and components, driving costs higher,” says Yelena Maleyev, associate economist at Grant Thornton. “Pandemics are a reality and could supplant trade tensions as the number one uncertainty for the economy.”

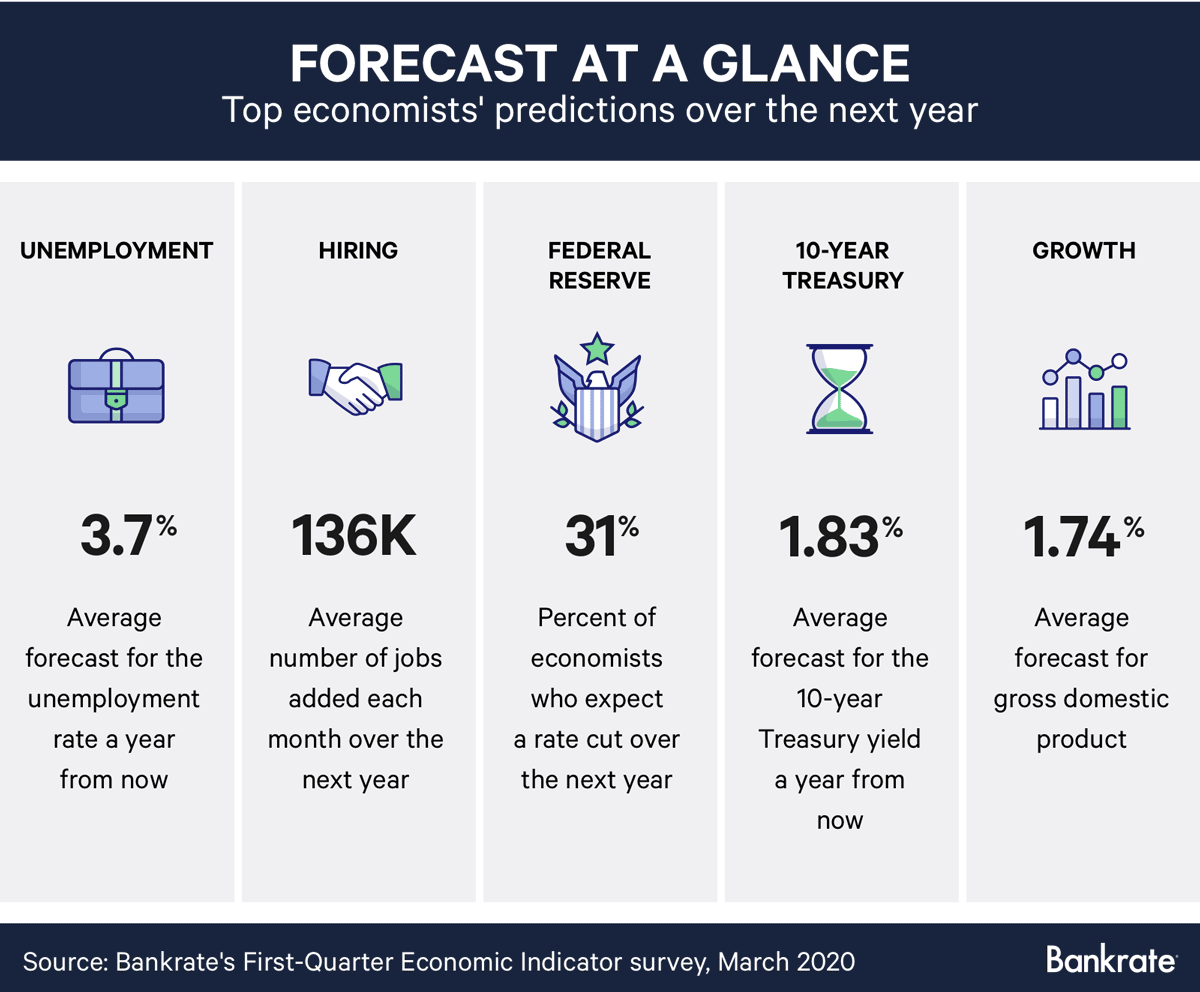

But the nation’s top economists aren’t expecting it to derail the record-long expansion — that’s as long as the fundamentals remain strong. Joblessness is expected to hold near its 50-year low, while employers are expected to add an average of 136,000 new jobs each month.

(Note: The economic situation surrounding the coronavirus is rapidly evolving. Respondents for Bankrate’s survey were polled between Feb. 12-21, days before the contagion showed signs of spreading more rapidly in areas outside of China. Those developments pushed the 10-year Treasury yield to all-time lows and prompted the Fed to institute its first emergency rate cut in more than a decade.)

Key takeaways:

- Global coronavirus risks could spill over to U.S. economy

- Experts expect lower unemployment rate than previous survey periods

- 10-year Treasury yield forecasted to edge back up

Experts increasingly pessimistic about U.S. economy

The Federal Reserve seemed committed to keep interest rates steady during the election year, after reducing rates three times in the year earlier to supplant slowing global growth and risks associated with the U.S.-China trade war. Storm clouds appeared to have cleared after Washington and Beijing reached a “phase-one” trade deal, but a new overhanging economic threat has taken over with the coronavirus.

That’s led the majority of economists (or 88 percent) to say that risks for the U.S. economy over the next year to year-and-a-half are tilted toward the downside. That compares with 81 percent in the prior quarter.

Only one respondent said risks were well-balanced, while just one said risks were tilted toward the upside.

“Nearly as soon as some of the economic uncertainty associated with trade disputes had diminished, fears have mushroomed surrounding the coronavirus outbreak and the associated impact on financial markets, businesses and consumers around the globe,” says Mark Hamrick, Bankrate’s senior economic analyst. This is why risks are still seen as tilted toward the downside.”

Economists expect continued job growth, low unemployment

But despite the storm clouds on the horizon, economists expect the robust job market to continue because the U.S. economy is chugging along steadily. Inflation has shown no signs of picking up persistently past the Fed’s 2 percent target. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has been hovering below 4 percent and has held near half-century lows since July 2018.

On the job market front, the tides won’t change all that much, according to experts. The average unemployment rate forecast is 3.7 percent and higher than what economists estimated during the fourth quarter of 2019. It’s also in line with data from the Department of Labor, with joblessness nationwide registering at 3.6 percent in January.

At the same time, the average prediction for job growth among economists showed that they expect it to slow from its current six-month average (which was about 206,000, as of January according to the Labor Department). But experts are reportedly more upbeat about the job market compared with previous survey periods. In the third and fourth quarter of 2019, economists expected employers to add 126,000 and 119,000 jobs each month, respectively.

“The job market should remain strong with more people continuing to gradually come off the sidelines into the workforce,” says Lynn Reaser, chief economist at Point Loma Nazarene University. “Companies will continue to compete for skilled workers and wage increases will continue to pick up.”

Even so, don’t expect gross domestic product (GDP) — the broadest scorecard for the U.S. economy — to show blockbuster growth. Economists see GDP expanding by an average of 1.74 percent in 2020. Five respondents saw annualized GDP lower than 1.5 percent, while one saw it even lower: 0.8 percent, which would be the lowest since 2016.

“We expect much weaker growth in the first half of 2020,” says Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “There are still few signs that industrial production and business investment have turned the corner, and there is still much uncertainty surrounding the spread of the coronavirus and its implications for U.S. growth. If things get worse in China, the impact to growth for its trading partners and broader disruptions to global supply chains could impact US growth more significantly.”

Fed’s Powell: ‘Too early to say’ how much coronavirus will impact economy

The novel coronavirus led the Fed to institute its first emergency rate cut since the 2008 financial crisis, as well as its biggest single reduction since the U.S. economy plummeted into the depths of the Great Recession.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that the outbreak and subsequent measures to contain it will weigh on economic activity “for some time,” both globally and domestically. The significant tightening of financial conditions on fears about the virus’ economic impact also posed a threat to growth.

The extraordinary measures out of the Fed could be categorized as an insurance reduction, with officials wanting to get ahead of the contagion’s impact on the U.S. economy rather than waiting before the damage had already been observed. Some economists envision two scenarios: More cuts if conditions worsen, or a swift take-back if the outlook improves.

Before the coronavirus threat escalated, officials didn’t expect the current outlook to derail the Fed’s plans. The majority of economists (or 56 percent) said the U.S. central bank is likely going to hold interest rates steady through the end of 2020.

Even though the Fed instituted an unscheduled cut, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said during a press conference following the move that it’s still too soon to estimate the extent of the coronavirus’ impact.

That’s similar to the thesis from Powell’s February testimony to Congress. Powell said “it’s just too early” to estimate the extent of that impact, but what matters most to the Fed is, “What will be the effects on the U.S. economy? Will they be persistent? Will they be material?”

Nearly one in three economists (or 31 percent) said the Fed would be forced to cut rates just once between now and the end of 2020, while 13 percent said the Fed would reduce borrowing costs two or more times.

But that’s still significantly less than economists’ expectations in the fourth quarter of 2019. Nearly two in five (or 43 percent) looked for the Fed to cut rates two or more times, while just 38 percent foresaw no changes in rates over the coming year.

“I am concerned about knock-on effects from the coronavirus, as well as lingering weakness and ongoing U.S.-China trade talks and yet-to-be-started U.S.-E.U. trade talks,” says Robert Brusca, chief economist at Fact and Opinion Economics who formerly worked for the New York Fed.

Keep an eye on the 10-year Treasury

But there’s one clear corner of the economy that the coronavirus outbreak has already impacted: the bond market. The 10-year Treasury rate on Wednesday fell past 1 percent in intraday trading, its lowest ever, after the Fed’s emergency rate cut prompted investors to flee for safe haven assets. The 10-year yield has already come down substantially since news of the first coronavirus case reported on Dec. 31.

Rates on the 30-year mortgage, which track the 10-year rate, have trekked downward similarly, though not as dramatically. The 30-year fixed rate mortgage dropped from 3.9 percent at the end of December to 3.71 percent as of Feb. 26, according to Bankrate data.

Economists’ forecasts for the 10-year Treasury rate range from 1.4 percent to 2.2 percent for the first quarter of 2020, with the average forecast calling for 1.83 percent. That’s significantly higher than where the actual yield closed (1.45 percent) on Feb. 21, when the nationwide poll closed, but before news about the virus’ spreading broke out.

“Global growth is struggling after two consecutive years of slowdown,” says Scott Anderson, executive vice president and chief economist at Bank of the West. “The coronavirus adds another very powerful downside risk for 2020.”

What this means for you

Would-be homebuyers have a significant opportunity on their hands, given that mortgage rates have continued to fall from their already historic lows. Rates haven’t fallen as dramatically as the 10-year Treasury yield, meaning there’s a chance they could fall lower as the spread between the 10-year and the 30-year fixed rate tightens.

“Treasury yields have recently dropped on concern about slower global economic activity, helping to pull down mortgage interest rates,” Hamrick says. “Low rates are one of the few sure things in a world awash in uncertainties. With the market moves, there is opportunity for borrowers including those intent on buying a home or refinancing a mortgage.”

Homeowners, meanwhile, should consider whether refinancing makes sense at this time. Doing so could potentially shave hundreds of dollars off future monthly payments.

Economists don’t look like they’re expecting a recession in the intermediate term, but there are a fair of downside risks associated with the coronavirus. While the good times are still rolling on, it’s the perfect opportunity to build up your emergency savings and pay off high-cost debt.

“There’s seldom an inopportune time to save for emergencies and to pay down debt,” Hamrick says. “We know that slightly less than half of Americans have more emergency savings than credit card debt more than a decade into the economic expansion. This indicates there’s more work to do on the savings front.”

Methodology

The Fourth-Quarter 2019 Bankrate Economic Indicator Survey of economists was conducted Feb. 12-21. Survey requests were emailed to economists nationwide, and responses were submitted voluntarily online. Responding were: Scott Anderson, executive vice president and chief economist, Bank of the West; Scott J. Brown, chief economist, Raymond James Financial; Ryan Sweet, director of real-time economics, Moody’s Analytics; Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist, Markstein Advisors; Robert Dietz, chief economist, National Association of Home Builders; John E. Silvia, president, Dynamic Economic Strategy; Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist, Oxford Economics; Mike Fratantoni, chief economist, Mortgage Bankers Association; Yelena Maleyev, associate economist, Grant Thornton LLP; Lindsey Piegza, Ph.D., chief economist, Stifel; Lynn Reaser, chief economist, Point Loma Nazarene University; Joel L. Naroff, president, Naroff Economic Advisors; Robert A. Brusca, chief economist, FAO Economics; Steven Williams Rick, chief economist, CUNA Mutual Group; Jim O’ Sullivan, chief U.S. macro strategist, TD Securities; and Tenpao Lee, Ph.D., professor of economics, Niagara University.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.