Fed signals near-zero rates here to stay through at least 2022

The Federal Reserve left interest rates alone and signaled plans to keep them pinned at zero through 2022, suggesting U.S. central bankers foresee the financial system needing support for years to come as it climbs out of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Policymakers on the U.S. central bank left their key borrowing rate in its current target range of 0-0.25 percent. It’s the Fed’s main lever for influencing the economy, serving as a benchmark for how much it’ll cost you to borrow and how much you’ll be paid to save — from rates on credit cards and auto loans, to yields on savings accounts and certificates of deposit (CDs).

“The virus and the measures taken to protect public health have induced sharp declines in economic activity and a surge in job losses,” Fed officials wrote in their post-meeting statement on Wednesday. “The ongoing public health crisis will weigh heavily on economic activity, employment, and inflation in the near term, and poses considerable risks to the economic outlook over the medium term.”

The move was widely expected, months after the coronavirus pandemic upended the global and domestic economy. Fed officials have been working nonstop since mid-March to help buffer the financial system from the pandemic-induced fallout. Efforts to contain the spread shattered the longest economic expansion on record, as states imposed stay-at-home orders to keep as many people at home as possible.

When businesses closed and factory floors shut down, the U.S. central bank slashed interest rates to zero, broke out the playbook from the 2008 global financial crisis and found ways to get credit to businesses and municipalities throughout all corners of the financial system.

“The Fed has taken rates to zero percent, and now they’re working to convince everyone that rates will remain at these levels well into the future,” says Greg McBride, CFA, Bankrate chief financial analyst. It’s “amid an environment of elevated unemployment, lower inflation and an economy that won’t return to pre-pandemic size until sometime in 2022.”

What the Fed is forecasting

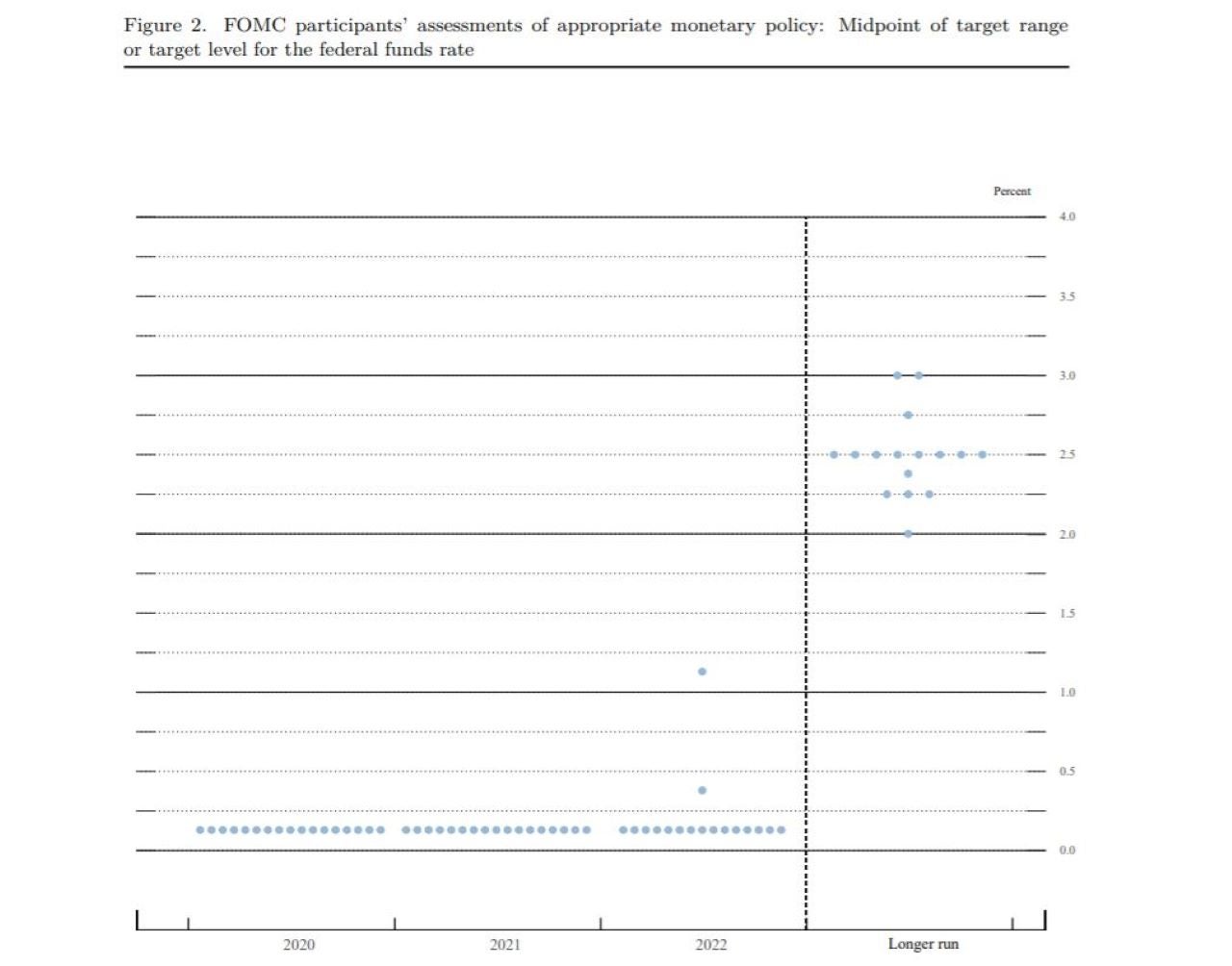

Beyond the Fed’s June rate decision, officials also updated their rate projections for the first time since December. According to the forecast, the Fed isn’t penciling in any rate moves through 2022, with only two of the Fed’s 17 officials expecting that the U.S. central bank will be able to raise rates in 2022.

Unemployment is expected to be at 9.3 percent in 2020 and 6.5 percent a year from now, according to officials’ median estimates, suggesting joblessness won’t be near its half-century lows seen in February, just before the pandemic. Officials expect the U.S. economy to contract by 6.5 percent this year and rebound by 5 percent in 2021, suggesting forecasts for a V-shape recovery aren’t on the table. Inflation is forecasted to be 0.8 percent by the end of the year.

“Yes, we’ve had some economic indicators that have surprised to the upside lately,” McBride says. “But calling this a V-shaped recovery at this point is like calling a no-hitter in the first inning.”

The U.S. central bank in 2015 started hiking rates following the Great Recession once unemployment fell to about 5 percent. Powell told journalists during a press conference after the rate decision that the Fed would be willing to let it fall even lower than that. He spelled out reasons that include a little-to-no threat of inflation as well as concerns that many Americans may lose touch with the labor force as the pandemic threatens business solvency.

The Fed would “welcome very low readings on unemployment just based on what we saw in the last expansion,” Powell said. “We aren’t thinking about raising rates. We aren’t even thinking about thinking about raising rates.”

It suggests the Fed will be walking a tightrope in the years ahead, one that includes both helping the economy fend off the coronavirus crisis, as well as grappling with the changing labor force dynamics that sparked a major Fed policy reversal in 2019.

“They’re going to be laser-focused on the labor market recovery and that is going to be the bar for raising rates,” says Tom Garretson, CFA, fixed income portfolio strategist at RBC Wealth Management. “It’s a situation where the Fed is not going to entertain the idea of raising rates until their estimates of full employment” are in full view.

Officials see financial conditions as improving compared to where they were in mid-March, but pledged to keep buying Treasury securities and agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities at at “at least” their current pace. Credit spreads widened in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, as investors flocked for safe-haven assets such as cash.

But continued support for the U.S. economy also includes keeping the Fed’s credit faucet running. Officials have created 11 different emergency lending programs to get cash to both Main Street and Wall Street. They signaled no appetite to let the tap run dry anytime soon.

Challenges of the Main Street lending program

One of those facilities — its Main Street lending programs — is new territory for the Fed. Offering three loan options, the catalog has gone through two revisions since announced on April 9. Powell initially said the program would go live at the beginning of June, but officials are still in the process of crafting what the program will look like, so it can provide optimal support.

A chorus of voices have echoed that the Fed might not be best suited to provide small- and medium-sized businesses with support. Firms may be hesitant to take on debt, given that the Fed can only provide loans, not grants.

Powell mentioned that the facility had not lost its effectiveness, given how long it’s taken to draft up the program, as it’s in the “final run up” of scaling it out.

“This has been a challenging project,” Powell said. “We’re going to be prepared to adapt further, if we need to.”

Though the officials provided Fed watchers with a strong signal about keeping rates at rock bottom, U.S. central bankers didn’t provide more specific forward guidance, and Powell voiced reasons to hold off on yield-curve control, for now. But don’t rule it out just yet, Garreston says.

“It’s probably the most likely unconventional policy tool they could bring in,” says Garreston, who expects the Fed would decide to cap rates on U.S. Treasurys as far out as the 5-year. “They’re still in elevated levels of uncertainty. They can look at everything they’ve done at this point as, ‘We bought ourselves some time; we bought the economy some time. If more is needed, we can wait until meetings later this year.’”

U.S. economy facing a sharp recession

The Fed’s decision comes just days after the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee declared that the U.S. economy is in a recession — one of the fastest decisions in the history of the academic panel, which has the sole authority over declaring when downturns start and end.

It represents the downward spiral that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and Co. have been forced to grapple with inside the world’s most powerful central bank. What was generally one of the best times in decades to be a Fed official became one of the most challenging and pressing in a matter of weeks.

Beyond the loss of lives and health hardships, the labor market was the coronavirus’ next biggest catastrophe. Months after holding at the lowest levels since the 1960s, joblessness is now at its highest since the Great Depression. Employers cut more than 22 million positions between March and April, while 1 in 4 individuals who were working in February have applied for unemployment benefits over the past 12 weeks.

The U.S. job market did show signs of recovering in May, with the unemployment rate edging down to 13.3 percent and employers adding 2.5 million new jobs, but it’s in nowhere near the shape it was at the start of 2020.

Per every job opening, there’s about 4.6 individuals who are unemployed, according to Labor Department data, signaling it’s a challenging time to be a jobseeker. Joblessness is expected to hover around 10 percent a year from now, while the U.S. economy is projected to add about 470,000 thousands every month for the next year, according to Bankrate’s Second-Quarter Economic Indicator poll.

The U.S. economy is also contracting by levels never seen before. The financial system shrank by 5 percent in the first three months of 2020 and is projected to collapse by 48.5 percent in the second quarter, according to estimates from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker on June 9.

What this means for you

The Fed’s decisions aren’t ones to be ignored, both at a broader and individual level. Credit is the lifeblood of the U.S. economy, and your financial decisions can be deterred or encouraged depending on how much it’ll cost you to borrow.

Generally speaking, when interest rates are low, it’s a good time to borrow money. If you’re thinking about making a big-ticket purchase, such as buying a car or a home, taking out a loan should be the cheapest it’s been in nearly half a decade.

But the script is flipped, given the uncertainties facing the U.S. economy. Now’s the time to prioritize building up your emergency savings because experts don’t know how long the hardship will last. You’re at a higher risk of losing your job during a downturn, and an emergency savings fund can be a crucial way to backstop your finances if the checks stop coming.

Experts recommend building up a buffer of cash worth about six months of your expenses in a liquid and accessible vehicle, such as an online savings account. Shop around for the best rate and account that fits your needs. Many yields on the market are still higher than the national average offered at traditional brick-and-mortar banks.

Meanwhile, it’s a good time to refinance your mortgage if you’re a homeowner, which could potentially shave hundreds of dollars from your monthly payment that frees up more money to be stashed away. If you’re carrying high-cost credit card debt, consider whether a balance transfer card is right for you.

Featured image by Mark Makela/Stringer of Getty Images.

Learn more:

- Winners and losers from the Fed’s latest decision

- 3 ways savers can handle falling interest rates

- Here’s what to do if you’re still jobless by the time your coronavirus unemployment benefits run out

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Fed holds interest rates steady, resisting pressure from Trump