Fed will begin tapering bond-buying stimulus, rates remain at near-zero

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday left interest rates alone but announced that it’s going to start gradually reducing its aggressive bond-buying program, the Fed’s first official move toward providing the financial system with less stimulus following the devastating impacts of the coronavirus pandemic.

- The Fed will reduce its current $120 billion monthly bond-buying program by $15 billion a month.

- Rates hold in their target range of 0-0.25 percent.

- Officials say supply and demand imbalances have created “sizable price increases” and expect that higher inflation is related to factors that are “expected” to be transitory.

What it means for: Mortgage rates | Savers | Borrowers | Investors

Beginning in November, the Fed announced it would reduce its monthly Treasury purchases to $70 billion and mortgage-backed securities to $35 billion, down from the respective $80 billion and $40 billion it had been buying since June 2020. If officials maintain that pace of buying $15 billion fewer assets for eight months, the Fed will no longer be buying any bonds by mid-2022.

“The committee judges that similar reductions in the pace of net asset purchases will likely be appropriate each month, but it is prepared to adjust the pace of purchases if warranted by changes in the economic outlook,” the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) said in its post-meeting statement, suggesting that the taper is open to flexibility depending on how the economy evolves.

Cutting interest rates to zero and buying massive amounts of assets are the two main ways that the U.S. central bank can prop up an economy during deep financial turmoil. The moves have kept mortgage rates at rock-bottom and made it easier for firms and consumers to take out loans in the middle of the worst recession in a lifetime.

The Fed’s tiptoeing away from those forceful measures marks a critical turning point for the U.S. economy and monetary policy. The move is seen as a vote of confidence amid an improving jobs picture, as employers in recent months show record demand to hire more workers. Yet, the wind down is also a testament to how much higher prices are climbing, with inflation rising at its fastest pace in nearly three decades. Hopes they’ll slow down anytime soon are diminishing.

“The Fed is taking the first step in a long, multi-stage journey of unwinding the extraordinary pandemic stimulus by starting to taper their monthly bond purchases,” says Greg McBride, CFA, Bankrate chief financial analyst. “A less accommodative Fed ultimately means higher interest rates, increased market volatility, and more pedestrian returns for stocks and real estate.”

The Fed’s taper: What it means for you

Mortgage and refinance rates

The bottom line is: If you have a fixed-rate mortgage, you won’t feel any impact from the Fed’s taper announcement. That’s because your interest rate is set for the entire life of your loan.

Yet, homebuyers and homeowners could still be impacted. Mortgage and refinance rates have been at historic lows throughout the coronavirus pandemic thanks to the Fed’s massive stimulus, and a Bankrate survey from October found that 74 percent of homeowners haven’t yet refinanced their mortgage.

Don’t miss out on your chance to refinance at a record-low rate. Experts say the refinance window could close at a moment’s notice given its close correlation to the 10-year Treasury yield, which could rise as the Fed buys fewer bonds.

Still, mortgage rates aren’t guaranteed to climb simply because the Fed is buying fewer bonds. Investors might judge it as a hawkish stance on inflation, which could cause yields to fall. The 10-year yield has already been volatile in recent days, falling at the end of October by the most since July.

“Mortgage rates will rise less than the 10-year Treasury yield and still be historically low and affordable in the context of the U.S. median sales price today,” says Sam Dunlap, chief investment officer at Angel Oak Capital Advisors, referring to rising mortgage rates. “What I do think tapering will do is slow down the pace of the momentum that you’re seeing in asset prices, especially in real estate and housing.”

Savers

Savings accounts and certificates of deposit (CDs) tend to rise and fall with the Fed’s short-term benchmark interest rate, the federal funds rate, which hasn’t moved from rock-bottom since March 2020.

With interest rates still on hold, the yields that savers earn by stashing away their cash are likely to remain at their lowest levels ever. Americans, however, are spending more now that the economy is opening back up, and some banks could start to offer consumers’ slightly higher rates as their total deposits dwindle.

You can still find ways to earn 10 times the national average yield by moving your money from a traditional brick-and-mortar bank to an online high-yield savings account.

Borrowers

Consumers with high-cost credit card debt will be better off if they can eliminate their overhanging balances now, while rates are still low. Analyze how much you would save in interest by estimating the cost of transferring your debt to a balance-transfer card.

Investors

Investments could whipsaw after the Fed’s taper announcement, and that market volatility has happened before. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke spurred a bond and stock market sell-off in June 2013 when he suggested that the economy would soon be strong enough for the Fed to start slowing down its monthly asset purchases. Experts say that might be avoided this time around, thanks to the Fed’s careful foreshadowing, but you’ll still want to keep a long-term mindset and avoid making any knee-jerk reactions to downdrafts in the market. Better yet, see any market downdraft as a buying opportunity.

Higher prices are the longer-term problem for investors. Manage a diversified portfolio with traditionally inflation-safe investments, from dividend-paying stocks and preferred stocks to real estate investment trusts. Meanwhile, avoid leaving too much cash in fixed-income investments, such as bonds, which tend to be more sensitive to price increases.

As Fed tapers, all eyes turn to officials’ next moves

The Fed is having to recalibrate its easy-money policies at a time when Americans are paying more for nearly all items in their budget, from groceries and gasoline, to rent, utilities and clothing. Consumer prices have increased at a near 13-year high for six straight months, while the Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation is at its highest since 1991.

Inflation

Officials have long said that they saw higher prices in 2021 thanks to lingering supply chain disruptions and record demand coming out of lockdowns. But those bottlenecks are lingering for longer than the Fed expected, while labor shortages are prompting employers to boost wages. The risk is that higher inflation could become a permanent part of the post-pandemic world, at least while the virus lingers. Experts say workers are also staying on the sidelines thanks to child care restraints, while others might have decided to retire or go into business for themselves.

Fed officials in their September projections showed that they expect inflation to hover above the Fed’s typical 2 percent inflation target for at least three more years.

In one of the key changes to the Fed’s post-meeting statement, officials began to indicate less confidence that today’s elevated rates of inflation will eventually fade, characterizing the recent price increases as related to “factors that are expected to be transitory.” Just in September, officials had said price increases were “largely reflecting transitory factors.”

“The Fed’s assessment of inflation continues to waffle,” McBride says. “They now say it is ‘expected to be transitory.’ Just like the subprime mortgage mess was expected to be contained?”

By tapering assets, the Fed would be slowly lifting its foot off the gas pedal, potentially lifting the cost of longer-term borrowing, such as mortgage rates.

“Employment remains stubbornly high — is quantitative easing helping with that, or is it just fueling asset prices?” Dunlap says. The latter is “one of the arguments that market participants are making.”

Interest rates

Rate hikes, however, would be the ultimate way to slow down the economy if officials worried that inflation were becoming too big of a problem for the financial system. A blunt instrument, rate hikes would make it more expensive to borrow money on anything from a credit card to a personal loan.

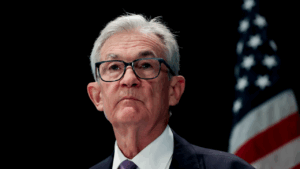

Yet, officials, including Fed Chair Jerome Powell, have indicated that now’s still not the time given ongoing economic weak spots, especially as nearly 5 million positions are still missing from the labor market and the labor force still has a gap of almost 3.1 million workers.

Rate increases also come with a cost. The U.S. economy is expected to grow at a record pace in 2021, most of that making up for the ground it lost during the pandemic. But the economic boom is already slowing, with the financial system growing at just 2 percent in the third quarter of 2021, the weakest pace of the recovery period.

Higher borrowing costs might dampen consumer demand more drastically than the economy can handle. Rising interest rates could also come with grave consequences for hiring, keeping Americans out of work for longer and worker pay increases subdued — similar to the environment that prevailed following the economy’s recovery from the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

“A supply issue is not something that will be fixed by raising interest rates, but which would definitely have the effect of cooling demand,” McBride says. “This may temper rate hike expectations in the second half of 2022 just a bit.”

Powell affirmed that the Fed doesn’t have the tools to solve supply restraints in a post-meeting press conference. Yet, kick-starting taper now does give the Fed more flexibility to get aggressive with rate hikes, should the sentiment change.

“We see shortages and bottlenecks persisting well into next year,” Powell says. “We have to be in the position to address that risk, should it create a threat of more persistent, longer-term inflation. That’s what we think our policy is doing now.”

The Fed in September was divided on its rate hike timeline, with half of policymakers now expecting to raise interest rates as soon as next year. Powell told journalists that the labor market hitting maximum employment in the second half of 2022 is “certainly within the realm of possibility,” which would largely be seen as the final hurdle before a rate hike.

“We’ll be patient, but we won’t hesitate,” Powell said of rate hikes.

Officials said they’d prefer not to be buying bonds if the time does come to increase interest rates, particularly because one is stimulative in nature, the other restrictive. By gradually tapping the brakes on stimulus now, officials may also have more time on their hands to keep eyeing the recovery, carefully making sure that they’re not withdrawing stimulus too forcefully.

“The Fed could be too little, too late is probably the greater risk, and they could end up having to play catch up later in the spring,” says Michael Farr, president and CEO of Farr, Miller & Washington. “The vast broad consensus from economists and a lot of investors is that more liquidity is going to exacerbate the inflationary problem, so slow it down, move modestly, but for God’s sake, move.”

Will Powell be reappointed as Fed chair?

The Fed is juggling its next steps as President Joe Biden is still deciding whether to give Powell another term as chair — or put someone else in charge. Speaking from a climate conference in Scotland, Biden said he hadn’t yet made a decision on who will be chair but indicated that the announcement should be coming “fairly quickly.”

Market participants broadly see the Fed chair choice as being between Powell and Fed Governor Lael Brainard, who’s even more dovish than Powell when it comes to setting interest rates and the lone Democrat on the Fed’s D.C. policymaking outpost.

In addition to Fed chair, Biden also has the chance to recruit three new people to the Fed’s board of governors, two of which would fill vice chair positions.

Learn more:

- Worried about surging inflation? Here’s 3 ways to protect your wallet from taking a big hit

- 5 ways the Fed’s decisions impact you

- How the Federal Reserve affects mortgage rates

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.