Secondary mortgage market: What it is and how it works

Key takeaways

- The secondary mortgage market is a financial marketplace where investors buy and sell bundled packages consisting of many individual loans, also called mortgage-backed securities.

- While you, the homebuyer, aren’t directly involved in it, the secondary market impacts your ability to get a mortgage and how much that loan costs.

- Borrowers can possibly benefit from decreased costs thanks to the secondary mortgage market.

When you get a mortgage, you might expect to repay your lender over the next 15 or 30 years. However, many banks and other lenders originate mortgages only to sell them to other investors. The secondary market plays a big role in your ability to get a mortgage and how much that loan costs, yet many homebuyers aren’t aware of it or how it works. Here’s what to know.

What is the secondary mortgage market?

The secondary mortgage market is a marketplace where investors buy and sell mortgages that have been securitized — that is, packaged into bundles of many individual loans. Mortgage lenders originate loans and then place them for sale on the secondary market. Investors who purchase those loans receive the right to collect the money owed.

Just like any market for securities, the value of mortgages on the secondary market depends on their risk and potential return. Higher-risk loans must offer higher returns, which is one reason why people with lower credit scores pay higher interest rates.

Primary vs. secondary mortgage market

The primary mortgage market is where borrowers get mortgages from lenders. For example, if you go to a local credit union and a couple of banks to get a quote for a mortgage, you’re participating in the primary mortgage market.

The secondary mortgage market doesn’t involve borrowers at all. Instead, it’s where lenders sell loans they’ve originated to investors.

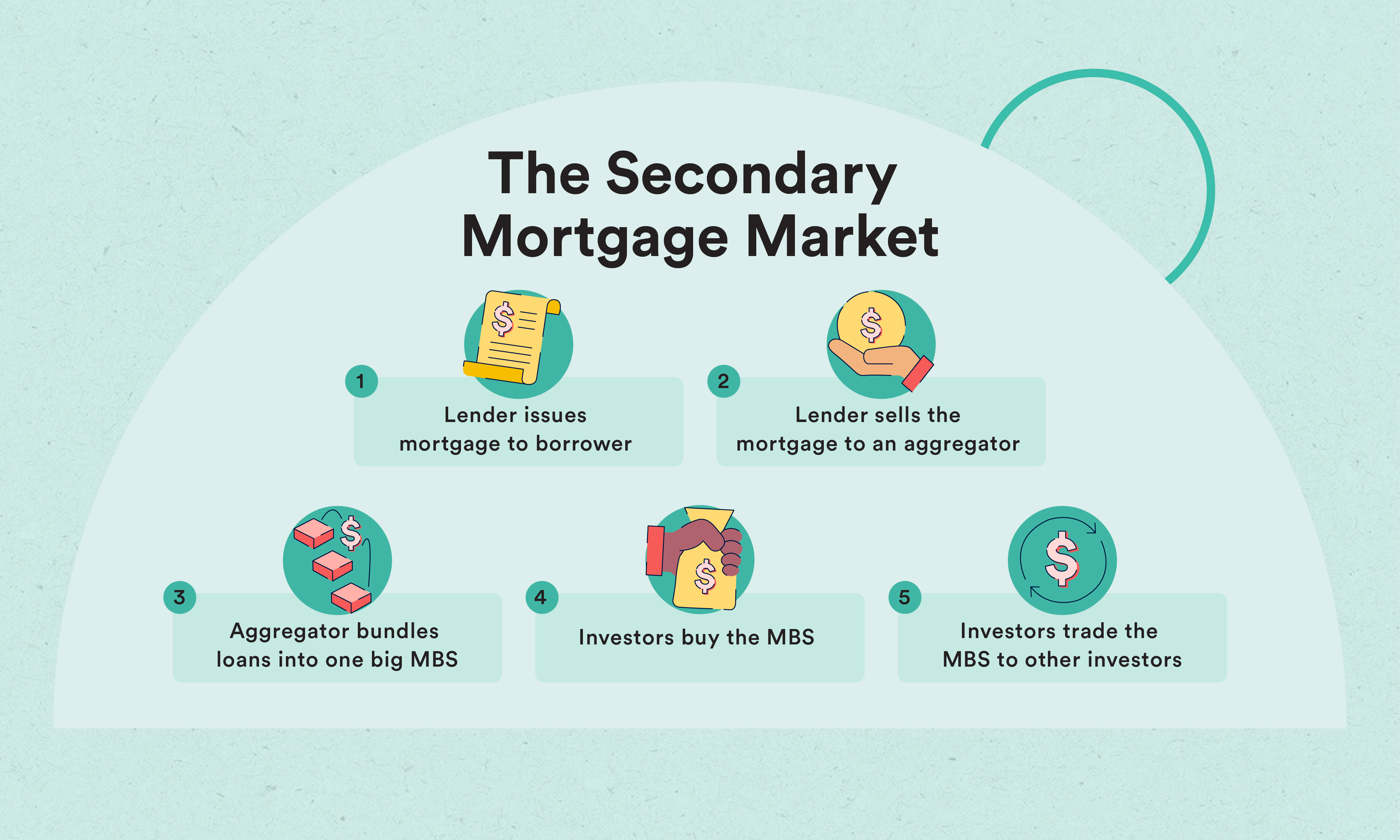

How the secondary mortgage market works

After a buyer receives a mortgage loan, the lender may sell it on the secondary mortgage market while continuing to service the loan for its borrower. If you have a primary mortgage and it is sold, you don’t have to worry because the terms of the loan and how it is serviced won’t change.

Many lenders sell loans to government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which can repackage the loans as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) or hold them on their own books and collect the interest from borrowers. Only conforming loans can be sold to GSEs because the loans must meet certain standards set by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which oversees Fannie and Freddie. These factors include:

- A maximum loan amount of $806,500 (for 2025) in most markets for a one-unit property, though it is higher (up to $1,209,750) in some expensive housing markets

- The down payment relative to the loan’s size, typically at least 3 percent

- The borrower’s credit score, usually at least 620 to 650

- The borrower’s debt-to-income (DTI) ratio, which should ideally be 36 percent or less

The demand for conforming loans helps push down the mortgage rates for borrowers who can meet the standards. Note that jumbo loans, which are larger in loan size, are not considered conforming loans.

1. A borrower takes out a loan

A homebuyer borrows money from a lender by taking out a mortgage (a conforming loan). The homebuyer gets cash to purchase the home, while the lender holds the buyer’s mortgage and a promise to be paid later at a specified interest rate.

2. The lender sells the loan to an aggregator

The lender sells the loan to a mortgage aggregator — often Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, who buy two-thirds of the mortgages in the U.S. The lender gets cash for selling the mortgage note, allowing it to use the capital to write another loan. The lender may retain the right to service the mortgage, a service for which it receives a fee.

The lender foregoes any mortgage repayments of principal or interest — because the aggregator now owns the loan after paying cash for it.

3. The aggregator bundles the loans into mortgage-backed securities

When an aggregator, like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, repeats the process of buying conforming loans, it amasses hundreds or thousands of mortgages across the United States. Then, it creates bundles of these packages, or “securitizes,” these loans into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in ways that include:

- Combining 1,000 mortgages into one series of MBS — making it less risky than buying a single mortgage — similar to a mutual fund that invests in many companies.

- Structuring the MBS into many different types of investment products and then sell “shares” in them.

- Creating a range of bonds that are very safe to a little risky, with lower payouts for the safer bonds and higher payouts for riskier notes.

- Structuring the payments to MBS bonds in ways that may appeal to certain investors. For example, many MBS only pay interest to investors, while some pay principal; others pay a combination.

In addition, if an aggregator has also purchased the mortgages’ servicing rights, it may retain them and service the underlying loans or sell them to a third party.

4. Investors buy the securities

There are a few types of investor groups that commonly purchase the MBS from aggregators; these include:

- Pension funds

- Mutual funds

- Insurance companies

- Other income-oriented investors

When the MBS is sold for cash, the aggregator typically uses it to buy more mortgage notes to repackage and resell. An investor can use the MBS to hold and collect income on (via mortgage payments) or sell it to another investor.

Once the MBS matures, and the investor is paid off, they can purchase another MBS or invest elsewhere.

Secondary mortgage market example

Imagine you take out a mortgage to purchase a new home. The lender gives you the funds to purchase the property, and you agree to pay the money back over a certain number of years. On the back end, however, the lender sells your mortgage to the secondary market for cash, giving the lender more capital to lend to more borrowers.

Ultimately, what the lender decides to do with your mortgage doesn’t impact you as the borrower, but a few things can happen to your loan once it is sold on the secondary mortgage market, including:

- The buyer holding your mortgage and collecting the interest

- Being bundled with other home loans and sold as a mortgage-backed security

Why does the secondary mortgage market exist?

Creating a completely new security from mortgages is a complex process, so why would the players involved in the mortgage market do this?

- Specialization: Because it allows lenders to slice up their mortgages, the secondary market also enables financial firms to specialize in various market areas. For example, a bank may originate a loan but sell it on the secondary market while retaining the right to service the mortgage.

- Allows lender to recoup money and lower risk: The secondary mortgage market allows loan originators to sell their loans after they earn money in fees on the loan, allowing them to recoup the money they loaned out, sell more mortgages and reduce their risk exposure. Even if the lender decides to keep the loan it originated, it benefits from having an active and liquid secondary market where it can sell its loans or servicing rights.

- Investors can purchase MBSs: The secondary market allows investors to purchase mortgage-backed securities, which pay a fixed interest rate, are viewed as a relatively safe investment and typically have higher yields than U.S. government bonds.

Overall, the secondary market creates benefits for each economic player — including borrowers, investors, banks/lenders, aggregators and rating agencies.

How the secondary mortgage market benefits homebuyers

Homebuyers benefit from their lenders participating in the secondary mortgage market in the following ways:

- Keeps mortgage rates low and equitable

- Allows borrowers to refinance at any time and without penalty in many cases

- Lenders can offer longer loan terms to borrowers

- The sale of mortgages provides cash to lenders so they, in turn, can offer more loans to potential homebuyers

Pros and cons of the secondary mortgage market

Advantages and disadvantages of the secondary mortgage market include:

Pros

- Lower costs: Borrowers can potentially benefit from lower expenses because of the secondary mortgage market.

- Investors can pick and choose loans: Investors (including institutional players such as banks, pension funds and hedge funds) get exposure to specific kinds of securities that better meet their needs and risk tolerance.

- It keeps money moving: Lenders can move certain loans off their books while retaining other loans that they’d prefer to keep. It also allows them to use their capital efficiently, generating fees for underwriting mortgages, selling the mortgage and then using their capital again to write a new loan.

- Aggregators collect fees: Aggregators such as Fannie and Freddie earn fees from bundling and repackaging mortgages and structuring them with certain attractive characteristics.

Cons

- It can come with risk: Mortgage-backed securities are not without risk. If borrowers default on their loans, investors could lose money, and the economy could take a hit.

- Impact on returns: Investors’ returns can also be negatively affected if borrowers refinance or pay back their loans quicker than expected.

- Strict eligibility criteria: GSEs have strict criteria for what types of loans they’ll guarantee in the secondary market, so lenders usually won’t issue loans outside of these parameters. As a result, borrowers with poor credit scores may not qualify for a loan, or if they do, they’ll likely face higher interest rates.

Bottom line

The secondary mortgage market is a financial marketplace where investors and lenders buy and sell mortgages via mortgage-backed securities, which are made up of many individual mortgage loans bundled together.

Lenders benefit from the sale of mortgage loans to the secondary market, allowing them to recoup the money they originally loaned out and offer more mortgages to borrowers. Meanwhile, investors can benefit by adding a relatively safe investment to their portfolio.

The secondary mortgage market can also positively impact homebuyers because it keeps mortgage rates relatively low and equitable and allows lenders to offer longer loan terms for repayment.

FAQ about the secondary mortgage market

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.