5 key themes to watch for at the Fed’s September meeting

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell is saddled with an unusual dilemma: How do you fend off a recession while also dismissing fears that it’s on the horizon?

That’s a tightrope U.S. central bankers are likely going to have to walk next week, with officials poised to cut interest rates for a second straight meeting on Sept. 17-18. It would be the first such consecutive reduction since the economy was on the brink of the Great Recession, in September and October of 2007.

In the weeks leading up to the meeting, policymakers have reiterated that the U.S. economy is in a good place and that the future looks bright. Hiring in the U.S. is still on firm footing, while continued wage gains have helped boost incomes and consumer spending.

They’ve noted, however, that the outlook isn’t free from risk. Trade wars are denting business confidence and investment, while growth is slowing globally. Central bankers around the world are lowering rates, and the Fed has made it clear that it’s time to take action.

“The Fed has, through the course of the year, seen fit to lower the expected path of interest rates. That has supported the economy,” Powell said on Sept. 7 during public remarks in Zurich. Switzerland. “That’s one of the reasons why the outlook is still a favorable one, despite these crosswinds we’ve been facing.”

Another rate cut means another direct impact on your wallet, whether you’re a borrower, saver or investor. Credit card rates, auto loans and home equity lines of credit (or HELOCs) will likely fall, as could the yields on your savings accounts and certificates of deposit.

Here are five key themes to prepare you for those adjustments, when the Fed makes its next interest rate announcement on Sept. 18 at 2 p.m. in Washington.

1. Look for a rate cut by a quarter percentage point

Powell’s comments in Zurich failed to walk back the expectation that a rate cut is coming, meaning U.S. central bankers are comfortable with the public expecting it to happen.

But just because the Fed looks like it’s going to lower rates again doesn’t mean it’s something they expected to be doing. On Aug. 1, just a day after the Fed reduced borrowing costs to a range between 2 percent and 2.25 percent, President Donald Trump escalated the trade war with China by slapping additional tariffs on $300 billion worth of imports from the Asian nation. Then, about a week later, White House officials announced another round: 10 percent duties on $112 billion worth of imports starting Sept. 1 and 10 percent tariffs on $160 billion beginning Dec. 15. Markets have been choppy in the weeks since.

“Had we not had further deterioration in the China-U.S. trade talks a few weeks after the last Fed ease, they probably would’ve been on a hold mentality,” says Tony Bedikian, managing director and head of global markets at Citizens Bank. “But because we’ve had a lot of volatility on and off of what’s going to happen with these talks, the Fed is going to have to re-evaluate further.”

Meanwhile, other economic signals are flashing warning signs. The 2-year, 10-year Treasury yield curve — a closely watched recession indicator — inverted Aug. 14 for the first time since the recession. Manufacturing in the U.S. also contracted in August for the first time since 2016, with many experts saying the industry is in recession.

[READ: How is the U.S. economy doing? Here are 5 key signs to watch right now]

“The inversion of the yield curve, the indication of contraction in the manufacturing sector — certainly both of those give the Fed cover for another quarter-point cut,” says Greg McBride, CFA, Bankrate’s chief financial analyst. He added that the “risks on the trade front that prompted them to cut rates in July were further heightened the following day. That changed the landscape a little bit from the Fed’s standpoint regarding downside risks.”

It’s unlikely, however, that the Fed will take a more drastic step and reduce rates by half of a percentage point. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard is the only one who has indicated that he would support the larger cut. Meanwhile, there are still two other Fed officials who have publicly expressed they think it’s too soon to start cutting rates to begin with: Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Kansas City Fed President Esther George.

A more drastic step might also spook the market and the public by indicating that a recession is closer than they might think.

“A half-point cut sends the wrong signal,” McBride says. “It would do more harm than good by worrying people about where the economy is heading.”

2. Expect Powell to paint a positive picture about the U.S. economy

That’s exactly why officials will want to reiterate that the U.S. economy looks like it’s in good shape. It’s similar to the message Powell delivered in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, during the Fed’s annual monetary policy symposium.

“The outlook for the U.S. economy since the start of the year has continued to be a favorable one,” he told attendees on Aug. 23. “Business investment and manufacturing have weakened, but solid job growth and rising wages have been driving robust consumption and supporting moderate growth overall.”

Powell characterized the Fed’s rate cut in July as a “mid-cycle adjustment” during the Fed’s post-meeting press conference on July 31. He’ll likely continue using that phrasing on Sept. 18.

“They would prefer to not signal at this point that it’s a trend toward an easing path,” Bedikian says. “The jury is still out as to whether the economic data is actually going to worsen, particularly in the U.S. The Fed made it pretty clear that a recession is not in their forecast currently, which is why they would be against signaling that there was a new trend toward easing.”

Two consecutive cuts also doesn’t constitute as an easing cycle. However, if the Fed cuts rates a third time this year, and possibly in early 2020, then it arguably could be, says Robert Frick, corporate economist at Navy Federal Credit Union.

“The Fed isn’t going to telegraph if it’s an adjustment or a cycle, and we’ll just kind of know when it happens,” Frick says. “If the trade situation improves or other economic measures flip into the green from the red, then the Fed will give a lot of thought to whether it’s going to cut any more. But [in] our current situation, I fully expect two cuts, probably three.”

3. Will the updated economic projections forecast additional cuts?

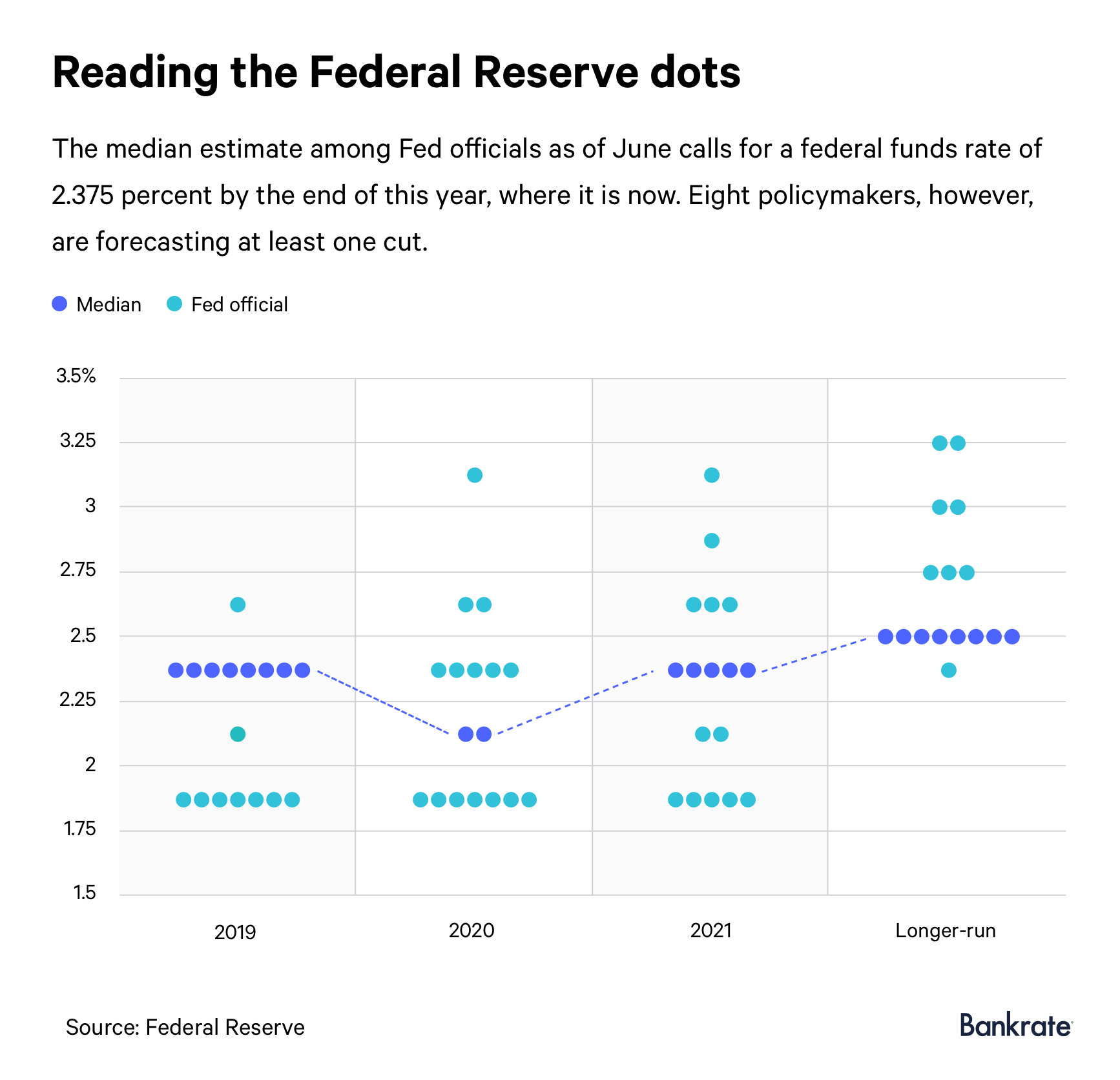

If you’re looking for clues as to whether the Fed could see additional cuts beyond the September meeting, you’ll find it in the U.S. central bank’s Summary of Economic Projections and its so-called “dot plot,” which is slated to be updated following the Fed’s announcement on Sept. 18.

The dot plot, which depicts each of the Fed officials’ forecasts for the midpoint of the federal funds rate at year end, showed that eight officials had penciled in cuts for this year. One official at the time only thought one cut would be necessary, while seven thought two 25 basis points cuts would be in store.

It’s likely that you could see some further shifts in the near-term federal funds rate outlook, as well as the longer-run rate, McBride says.

It’s likely that you could see some further shifts in the near-term federal funds rate outlook, as well as the longer-run rate, McBride says.

“There’s not going to be a consensus that rates are going to hold at this level and start to go back up in 2020,” McBride says. “I would expect the dot plot will be weighted toward additional rate cuts but reflect a range of differing views on the health of the U.S. economy and whether additional action is needed.”

That’s partially because Fed officials are not entirely aligned on whether cutting rates is necessary. In addition to Rosengren and George, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan has also said it’s important not to overreact to downside risks, noting that he’d prefer to avoid additional stimulus.

“I’d like to avoid having to take further action, but I think I’m going to have an open mind about taking action over the next number of months if we need to,” Kaplan said Aug. 22 in an interview on CNBC.

The dot plot is likely going to reflect those divisions among officials, and it may be even harder than usual to tell the path for policy in the year ahead. Even so, developments are always changing, so the dot plot may have a quick expiration date. But it might not be bad news.

“It’s useful that it illustrates how divided the Fed is,” McBride says. “It’s a positive economic indicator. If there was consensus that the Fed would continue cutting rates, that doesn’t exactly send a warm and fuzzy feeling about the economy. The fact that there is a lot of division and dissent within the Fed tells you that maybe the economy’s not so bad after all. Maybe the downside risks aren’t as great as might be feared.”

It’s also worth watching whether forecasts for the unemployment rate or growth edge lower in the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, McBride says.

4. Listen for questions about Trump’s recent attacks on Fed

But just as Fed officials haven’t been quiet in the weeks leading up to the next rate-setting meeting, neither has the president. Trump has tweeted 42 Fed-bashing tweets since the Fed cut rates on July 31, even going as far as deducing Powell as a greater enemy than President Xi Jinping of China.

Trump in a series of tweets on Wednesday recommended the Fed to lower rates to “zero or less,” and called officials on the U.S. central bank “boneheads.”

….The USA should always be paying the the lowest rate. No Inflation! It is only the naïveté of Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve that doesn’t allow us to do what other countries are already doing. A once in a lifetime opportunity that we are missing because of “Boneheads.”

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 11, 2019

His comments come on the heels of a controversial op-ed from former New York Fed President Bill Dudley, which was published in Bloomberg Opinion on Aug. 27. Dudley argued that the Fed shouldn’t cut rates in response to tit-for-tat trade disputes because it would only encourage Trump to continue the battle. The publication sparked criticism from policymakers on the Senate Banking Committee, including Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), who called for a hearing on Fed independence, citing fears that it would use monetary policy to meddle in the 2020 presidential election.

Powell and other Fed officials have since pushed back against the idea that politics of any kind enters the boardroom. He’ll likely reiterate that message even more.

“President Trump’s repeated badgering of Fed officials, calling for them to ease monetary policy despite near-target inflation, robust spending growth, and low unemployment, has one thing to be said in its favor,” says George Selgin, senior fellow and director of Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. “Assuming that these statistics don’t change dramatically, it offers the Fed a unique opportunity to prove that its much-ballyhooed independence is, after all, not just a fairy tale.”

[READ: Here’s what Trump can (and can’t) do when it comes to Powell and the Fed]

5. How a second rate cut might impact your money

Even with the Fed expected to cut rates by another quarter percentage point — which would bring the total rate cuts across both September and July to 50 basis points — it’s unlikely that you’re going to feel a substantial impact.

“The Fed raised rates nine times” since December 2015, McBride says. “Unwinding two of them still means rates were a lot higher than they were a few years ago. Unwinding a second, rolling back two of those rate hikes, just puts us back to where we were a year ago.”

Yields on CDs and savings accounts have already started to slide, in anticipation of more Fed easing. But even then, many accounts on the market are offering yields of 2 percent or higher, which is outpacing inflation. The best savings account rates pay more than 20 times what’s offered by a traditional, brick-and-mortar bank.

Mortgage rates have already fallen since before the Fed cut rates, breaching 5 percent in November 2018 to below 4 percent now. Consider taking advantage by refinancing, which could potentially shave a couple hundred dollars off your monthly payments.

And even though economists and Fed officials aren’t expecting a recession anytime soon, it’s never too late to start preparing.

“Regardless of the assessment, it’s important to take the steps necessary to put yourself on the best financial footing you can,” McBride says. “Pay down debt, pay off debt, and boost your savings — and in particular, boost your emergency savings. That goes a long way in the event that we do have a recession, at whatever point down the road that may materialize.”

Learn more:

- 7 ways to recession-proof your finances

- 5 ways the Fed’s interest rate decisions impact you

- Survey: Expect the Fed to cut rates at least two more times over the next year

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.