The surprising reasons home prices have held up in this recession

When the American economy plunged into recession this year, many homeowners braced for a repeat of the Great Recession. Such fears were logical. After all, the last time the U.S. economy shrank, home prices plummeted.

But this recession has played out far differently from the previous bust. Home prices kept rising even as unemployment soared. The combination of tight supply and robust demand has sparked bidding wars in many corners of the country.

While the coronavirus recession has been unusual in many respects, it’s completely normal in this important way: This downturn hasn’t hurt the housing market, at least not yet.

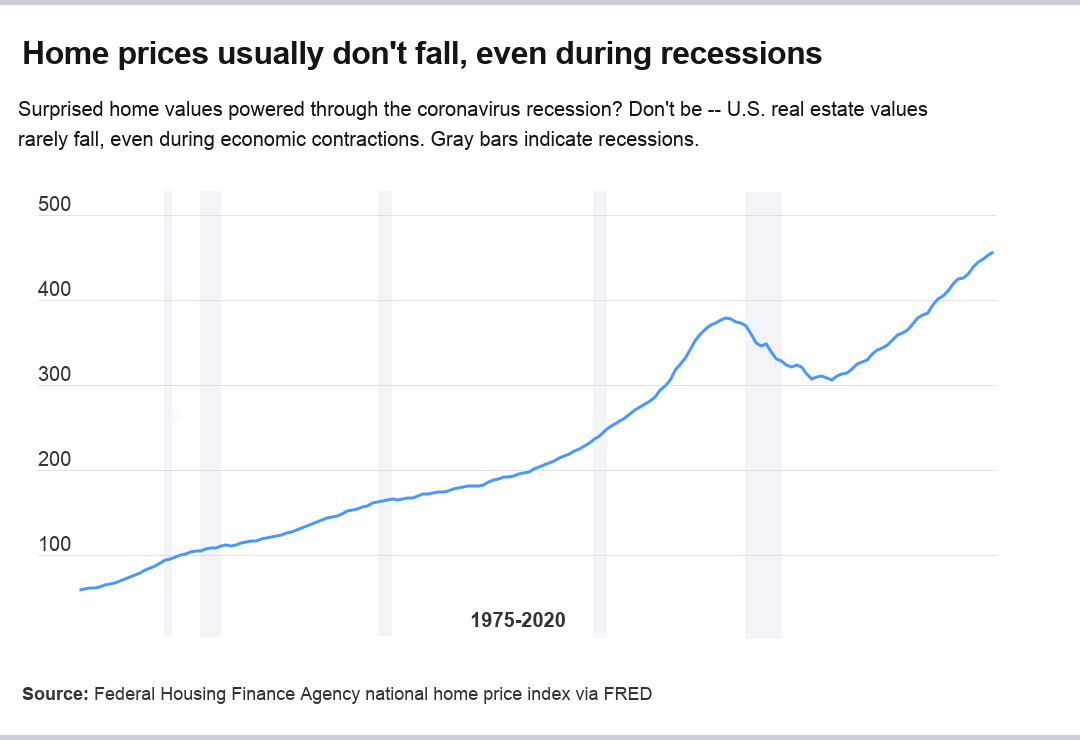

If the history of recent recessions is any guide, home prices might escape this economic contraction unscathed. That’s what happened in the four recessions preceding the Great Recession — home values were essentially unaffected.

Residential real estate usually weathers recessions because of the “contrasting crosswinds” that accompany downturns, says Lynn Reaser, chief economist at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego. Layoffs mount and incomes shrink, hurting demand for homes. But falling interest rates cushion some of the blow, propping up demand and allowing buyers to pay more for homes.

“While housing demand is still generally down during recessions, supply also falls as builders are reluctant to start new projects and face problems accessing credit,” Reaser says. “The net effect of lower housing demand but also lower supply is typically a negative but not devastating impact on price increases.”

How home prices have fared in recent recessions

Here’s a rundown of the housing market’s performance during economic downturns over the past four decades, based on the national home price index compiled by the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees lending giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac:

- 1980: Home values rose 5 percent during this short downturn in the final year of the Carter administration.

- 1982-83: Home prices rose 9 percent during this more protracted contraction.

- 1991-92: Values climbed 5 percent during the Gulf War recession. However, the economic hangover from that recession did hurt home prices in some parts of California and New England later in the decade.

- 2001: Values increased 2.7 percent during this short recession, which was spurred by the dotcom crash and worsened by the September 11 terror attacks. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan later said he feared more attacks and therefore kept rates low — setting the stage for the housing bubble.

- 2008-2009: The Great Recession was the outlier. From the start of 2008 through the third quarter of 2009, home values fell 11 percent.

Unlike the other four downturns, the Great Recession was propelled by a housing bubble. Values already had been falling from their bubble levels before the recession officially started, and they kept dropping after it ended. From the peak of home values in 2007 to the trough in 2012, national home values sunk 19 percent — and some homeowners in Arizona, Florida and Nevada saw their homes lose half their value.

Housing markets are local

It’s rare for home values to fall nationally, but it’s not as unusual for prices to plunge in local markets. Texans experienced that reality in the late 1980s and early 1990s, while Californians learned this lesson in the 1990s.

The oil boom and bust of the 1980s set up Texas and other oil patch locales for a housing crash. According to a study by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Houston home prices dropped as much as 22 percent compared to five years earlier. San Antonio experienced a five-year decline of as much as 17 percent, Austin prices fell as much as 25 percent and Midland values were off by 31 percent.

One Rust Belt market also took a hit in the 1980s. In Peoria, Illinois, home values fell as much as 17 percent that decade. The FDIC blamed job losses and a prolonged strike at Caterpillar, the heavy equipment maker that was headquartered in Peoria.

The Gulf War recession, meanwhile, took a toll on home prices in Southern California. In the years after that recession, once-hot California markets were hit by a decline in home prices as a result of downsizing in the defense industry. In the mid- to late 1990s, home prices in Los Angeles fell as much as 19 percent compared to five years earlier. The busts were as sharp as 18 percent in Riverside and 17 percent in Ventura, the FDIC says.

Some New England markets also felt sharp downturns in the 1990s. Home values in Manchester, New Hampshire, fell as much as 20 percent from five years earlier, while prices were off by 17 percent in Hartford, Connecticut, and by 16 percent in New Haven and Norwich, Connecticut.

While home prices are guided in part by high-level factors such as mortgage rates, they’re also intensely local. Regional wages and neighborhood building patterns play major roles in home values.

Why this recession is different from the last one

The Great Recession was the painful result of a housing party that included a spasm of speculation, a flood of irresponsible lending and an oversupply of new homes. None of those factors were in play during the four previous recessions, nor in the current downturn.

The coronavirus recession has unfolded amid an entirely different backdrop for the housing economy. The flood of foreclosures remains fresh in many Americans’ memories, so individual investors haven’t been quite as eager to jump into the housing market. What’s more, lending standards have remained strict, and new construction has been muted.

Meanwhile, this downturn began with mortgage rates already near record lows. Rates have fallen further, propping up home prices. And stay-at-home orders and remote work have propelled demand for bigger houses.

The coronavirus recession has been spurred entirely by the lockdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic. That makes it a new scenario in recent history. But this downturn is like most previous recessions in that the housing market is a bystander rather than a central actor.

“The coronavirus pandemic has rewritten the rules on housing and recession,” Reaser says, “at least for 2020.”

Learn more:

- Housing Hardship Index: See which states face most severe threat from coronavirus recession

- Massive stimulus could bring inflation at some point

- Mortgage rates at record lows

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like