The economy has avoided a recession so far — and it could be a nightmare for the Fed

The U.S. economy has remained surprisingly resilient against the most aggressively hawkish Federal Reserve in 40 years. That could be worrisome to officials at the U.S. central bank.

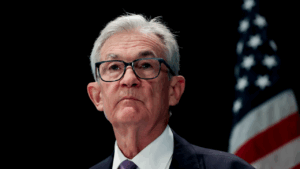

Fresh economic data released throughout the first two months of 2023 is starting to suggest that demand and inflation might not be slowing as much as previously thought. Fed officials — including Chair Jerome Powell — are now warning rates are likely going to rise even higher than they previously expected and stay there for longer.

“The data from January on employment, consumer spending, manufacturing production and inflation have partly reversed the softening trends that we had seen in the data just a month ago,” Powell said in a semiannual congressional testimony on Tuesday.

Employers added 517,000 new jobs in January, the biggest hiring burst in six months, while joblessness slumped to a new half-century low of 3.4 percent. Businesses are expected to have continued hiring at a robust pace even in February, though job growth is likely to have slowed by more than half from the blockbuster pace reported in the prior month.

Retail sales also rebounded sharply in January after a December slump. And worst of all: Prices heated up between December and January, after cooling from the previous month for the first time since the pandemic began.

The silver lining is that economists now aren’t so certain a recession could be around the corner. Goldman Sachs cut the U.S. economy’s recession odds over the next 12 months to 25 percent from 35 percent, according to a Feb. 6 note to clients. A National Association of Business Economics (NABE) poll from January, meanwhile, slashed its calls to 56 percent from 64 percent.

But for Fed officials hoping they could “softly” land the economy — code for gradually cooling demand and inflation without causing the financial system to crash in a “hard” recessionary landing — the slew of stronger-than-expected economic data is raising a new possibility: What if the Fed can’t land the plane at all?

“We’re moving in the wrong direction,” says Chris Campbell, chief policy strategist at the Kroll Institute and former Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Financial Institutions — a role Powell previously held. “While amazing for American families and the American economy in general, strong economic data is bad for the Fed in its goal to tame inflation.”

Hotter economy could mean even higher rates — and more economic pain for consumers

Policymakers’ top objective has always been throwing cold water on the hottest price pressures in four decades.

Fed officials have raised interest rates 4.5 percentage points so far since March 2022, a pace not seen since Jimmy Carter was president or Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” dominated the charts. Assuming the U.S. economy was starting to bend underneath the weight of monetary policy, officials in February lifted interest rates by a quarter of a point, the smallest amount in 10 months.

Policymakers had signaled plans to keep hiking rates by that smaller, more traditional amount until the Fed judges it’s time to be done. The Fed’s median rate projection from December estimated the U.S. central bank’s so-called peak “terminal rate” could be 5-5.25 percent. Seven officials, however, saw rates rising even higher than that level. Five officials put the Fed’s key interest rates in a 5.25-5.5 percent target range, while two saw rates climbing to 5.5-5.75 percent.

The Fed, however, submitted those forecasts before inflation and hiring heated up. A “no landing” for the U.S. economy could mean even higher rates — and possibly more aggressive hikes — are needed to get the job done.

The Fed won’t update those projections until its March rate-setting meeting, after which it’ll have one more employment and inflation report to analyze. Yet, Powell also joined Fed Governor Chris Waller in calls for a higher peak. Waller said in a pivotal speech on Friday that he’d support raising rates even higher than those two 5-5.25 percent and 5.25-5.5 percent ranges if hiring and inflation “continue to come in too hot.”

After seeing promising signs of progress, we cannot risk a revival of inflation. Wishful thinking is not a substitute for hard evidence, in the form of economic data.

— Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller

Will the Fed stick with quarter-point increases? Only time — and data — will tell

In speeches after the Fed’s February rate decision, non-voting Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester and St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said they were pushing for a larger half-point hike at the Fed’s February rate-setting meeting, adding larger increases should also be on the table for subsequent meetings.

“Nothing right now is leading me to think that I need to be really focused on that question at this point,” Mester said in a Feb. 16 call with reporters, referring to the debate on when to stop raising interest rates.

Powell said in his Tuesday address a faster pace of tightening could be warranted if the “totality of the data” were to keep showing the economy is running hotter than previously thought.

Even so, officials may prefer to keep raising rates in the more traditional quarter-point increments, for fear of making it appear like February’s downshift was a mistake, according to forecasts from Andrew Patterson, CFA, senior international economist at Vanguard. Patterson now sees the Fed lifting rates to 5.5-5.75 percent before it’s all said and done, the highest since 2001.

“You want to see a couple of months of data before you’re ready to call a change of trajectory,” Patterson says. Still, “we’re starting to see a slowdown in the pace of goods deflation, and services inflation is remaining relatively persistent. We want to see a change in the trend. The way to come about that is a somewhat higher terminal rate.”

The data has done much of the talking for investors. Up until early February, market participants expected the Fed to lift borrowing costs to 5-5.25 percent before cutting them down to 4.75-5 percent by the end of the year, according to CME Group’s FedWatch. That’s been replaced with considerably more aggressive expectations, with rates largely seen as peaking at 5.5-5.75 percent by June.

Soft, hard or no landing? ‘The plane has to land at some point’

Vanguard’s Patterson says he prefers to stick with the term “later landing” over “no landing.” His reasoning: The plane has to land at some point. Without it, inflation might not get back on track.

The Fed sees risks on both sides. Not doing enough could give inflation time to heat back up even more. With employers in front-facing leisure and hospitality industries still clamoring for more workers, businesses could keep lifting wages and pass along those higher labor costs to the consumer if there’s no progress in loosening the job market. Such a string of inflation — known as a wage-price spiral — becomes difficult for the Fed to untangle.

Powell has repeatedly said since November that job growth remains “far in excess” of the pace needed to accommodate population growth over time.

“To restore price stability, we will need to see lower inflation in this sector, and there will very likely be some softening in labor market conditions,” Powell told Congress on Tuesday.

Higher rates mean a bumpier economy and more expensive borrowing costs

The higher rates climb, however, the more disastrous it could also be for consumers. Home equity lines of credit, auto loans, credit cards and more typically rise in lockstep with moves from the Fed. Those borrowing costs are already at the highest in more than a decade, while credit card rates have been hovering at all-time highs. The average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has also jumped for two straight weeks amid the recent pick-up in inflation.

A blunt instrument, more expensive borrowing costs designed to slow economic activity and spending could also weigh on business growth and investments. In other words, engineering higher joblessness and slower hiring may be the only way the Fed knows how to slow inflation.

The Fed could benefit from informing markets and consumers how it expects to achieve its 2 percent inflation objective without inflicting a severe recession, says Robert Hetzel, an economist at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center who formerly worked at the Richmond Fed during the previous Great Inflation in the 1970s and ‘80s. Part of the problem, economic data comes with a lag, and officials might not know whether they’ve done enough to cool inflation until the labor market has already been dealt a blow.

“We don’t have a strategy to guarantee to the public that we’ll come out of it without repeating the mistakes of the ‘70s,” he says. “We have a long way to go. The issue is, do we repeat the 1970s and keep raising rates until we get a real recession? Is there some way to lower inflation without putting the economy through a real recession?”

Even if a not-so-severe recession akin to a “soft” economic landing is possible, joblessness may still increase. Officials’ most recent projections put the unemployment rate at 4.6 percent by the end of the year, more than a percentage point higher than its current level. Inflation, meanwhile, was seen as dropping to above 3 percent.

“Soft” landings might mean people don’t have to hunt as long for their next opportunity. Yet, any style of landing may feel bumpy for the Americans who feel pain as a consequence of the Fed’s inflation fight.

“Seems like some people are trying to fight gravity,” Campbell says, referring to the prospect of a “no landing.” “The economy is going to land somewhere; we just don’t know where it’s going to land. If you’re impacted, there is no soft landing.”

-

Higher Fed interest rates lead to more expensive borrowing costs, more lucrative yields on savings accounts and higher recession risks.

With higher rates here to stay, consumers should think about limiting how fragile they are to rising rates — and finding ways to take advantage of the benefits of more expensive borrowing costs that could come in handy during a downturn.- Refinance variable-rate loans into fixed: Don’t be a sitting duck to rising interest rates with adjustable-rate loans.

- Chip away at high-cost credit card debt: Not paying off your balance in full each billing cycle is likely costing you hundreds — if not thousands — of extra dollars a month. That goes up every time the Fed hikes rates.

- Work on boosting your credit score: Your credit history is the single most important factor that guarantees whether you’ll get a bank’s cheapest — or highest — rate from a lender.

- Park your money in a bank account where your cash is welcomed with open arms: Top-yielding online banks are paying more than 4 percent annual percentage yield on their depositors’ cash, compared with the 0.23 percent national average yield. On a $10,000 balance, that could be the difference between more than $400 in annual interest versus $23.

- Think about furthering your career or income-earning opportunities to recession-proof your finances: See if you can monetize your side hustle or hobby to make extra cash that you can sock away for a rainy day.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Fed lowers interest rates with surprising jumbo half-point cut