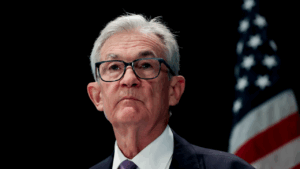

As Trump eyes Powell’s successor, the Fed moves toward another rate cut

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has endured nearly every crisis a central banker can face during his eight years at the helm of the Fed: blistering public attacks during President Donald Trump’s first term, an unprecedented global pandemic that forced rates to near-zero, the worst inflation in 40 years, tariffs and the most intense round of political pressure yet.

Now, the one thing the chief central banker has long been lauded for — his ability to forge consensus across a committee with wildly different views — is being tested.

The Fed is widely expected to cut interest rates for the third straight time when policymakers gather for the final meeting of the year on Dec. 9-10. Multiple policymakers, however, could dissent for the fourth straight meeting.

Some regional bank presidents have publicly opposed lowering borrowing costs while inflation drifts further from the Fed’s target. Others on the Fed’s board of governors have pointed to a deteriorating job market, pushing back on the Powell-backed approach to ease policy slowly and carefully.

Taken together, these perspectives paint a picture of a splintering committee, with policymakers who have historically sided with Powell now starting to break ranks. That’s all happening as Powell’s tenure as chief central banker draws to a close and Trump appears poised to name his successor, adding yet another layer of uncertainty over where the Fed could be headed next.

The new chair-in-waiting shouldn’t be in a hurry to politicize the role, and maintaining the Federal Reserve’s independence will be important for keeping the bond market, investors and Congress calm.— Stephen Kates, CFP, Bankrate financial analyst

Will Powell get the votes for a third straight interest rate cut?

The toughest division of Powell’s career as chief central banker isn’t his fault. It reflects competing economic challenges. Workers are finding it tougher to get new jobs, but inflation has also moved away from the Fed’s target every month since April.

“Where the economy is now, that makes disagreement more likely,” says Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at BNY Investments. “When you’re at an inflection point, you’re more likely to have differences of opinion about your forecast.”

The Fed had also signaled for months that a third straight rate cut would be a close call. In September, the prospect of cutting rates three times in 2025 appeared to come down to just one official. Records from the Fed’s most recent meeting in October also revealed that “several” policymakers were against lowering the Fed’s benchmark rate again in December.

A rate cut in December seemed unlikely until public remarks from New York Fed President John Williams, one of Powell’s closest allies, who said on Nov. 21 that he was more worried about a weakening labor market than inflation. The following week, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly publicly backed a December rate cut.

Daly doesn’t vote on interest rates this year, but her remarks were still notable for showing that the pro–rate-cut voices hadn’t died out — even after weeks of officials opposed to a December cut dominating the conversation.

Markets got the message. In just a two-week span, expectations swung wildly from a roughly 30 percent chance of a rate cut in December to about a 90 percent probability, according to CME Group’s FedWatch tool.

“It does seem like a planned thing to go out and shift the markets back to expecting that cut,” says Luke Tilley, chief economist at Wilmington Trust. “When Williams spoke, it sort of gives them the nod to the way that Powell is thinking about it.”

Powell is unlikely to sway everyone to his side. Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid dissented against October’s rate cut and is expected to disagree again. Fed Governor Stephen Miran, meanwhile, argues the Fed should be cutting more aggressively.

The rest of the voters — including Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee, Fed Governor Lisa Cook, and Vice Chair Philip Jefferson — have signaled that their minds aren’t fully made up.

For Powell, the choice over how to steer the economy may come down to which problem he feels could be harder to fix. Hinting at how Powell may be weighing those risks, Daly said the Fed can get ahead of inflation more easily than it can get ahead of a deteriorating labor market.

But with Powell’s term ending in May 2026, the choice may also hinge on which legacy he would regret leaving behind the most: elevated inflation or an economy sliding into recession.

“Chair Powell is leaving the building,” Reinhart says. “He knows he will leave the building with inflation above goal. There’s nothing he can do about that. … But the economy going into a recession, that’s a bigger regret.”

A new Fed chair could make it challenging for the Fed to give clear signals

Trump has said he plans to announce his pick for the next Fed chair in “early 2026,” with White House National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett emerging as the frontrunner, according to reporting from Bloomberg. Powell’s time as Fed chair is officially up on May 15, 2026.

The advance notice isn’t unusual. President Barack Obama tapped Janet Yellen about four months before Ben Bernanke’s chair tenure ended, while Trump picked Powell about three months before Yellen’s term ended. The early announcement gives the Senate time for confirmation and the markets a heads up about the transition.

Yet, personnel changes at a time of intense division complicates the U.S. central bank’s ability to clearly signal where they’re heading next.

Fed watchers won’t just want to know whether policymakers cut in December but also if more cuts could be on the table in the months ahead. Officials usually give this so-called “forward guidance” at the final meeting of the year, when they update their quarterly economic estimates. Those projections are intended to show where all sitting policymakers expect interest rates could be by this time next year.

“The Summary of Economic projections doesn’t matter if the president names the chair next week or in three months,” Reinhart says. “If they’re talking about the year end 2026 policy rate, it’s a different FOMC.”

Markets could start tuning out Powell and tuning in to the nominee for clarity on the path ahead. Another risk for Powell is that his influence over the committee starts waning.

One of the fundamental jobs of the Fed chair is to steer the committee toward a consensus, which relies on what Reinhart describes as “soft power.”

Reinhart attended more than 100 FOMC meetings during his two decades at the Fed. In those meetings, he noticed dynamics he likens to the 1980s John Hughes film, “The Breakfast Club.” Every meeting had its “cool kids” table, where the officials with titles like chair or vice chair sat. And every meeting also had its “wannabes,” he says — policymakers who hope to move up to that table someday.

With Powell’s days numbered, he has fewer bargaining chips to win over the more hawkish members of the committee. One traditional option is offering up a “hawkish cut,” where the Fed lowers rates in December but suggests additional cuts after that aren’t guaranteed. That may no longer be a viable promise, as Trump considers Fed chair candidates who think interest rates should be lower.

“The chair’s ability to corral the group depends on their use of the soft power associated with the chair,” Reinhart says. “You want to be on the chair’s good side. However, if you know the chair isn’t going to be there more than a meeting or two more, some of that soft power erodes.”

Don’t wait on the Fed to take these 3 crucial steps with your money

If the Fed cuts rates in December, borrowing costs will be 1.75 percentage points off their peak of 5.25-5.5 percent, where they were up until the fall of 2024. But broadly speaking, the Fed’s benchmark is still higher than it was at any point since the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Consumer borrowing costs have edged down, but they likely still feel expensive to anyone who remembers shopping for loans when the Fed kept rates near zero during the pandemic.

Yet you can’t time the market. When the dishwasher breaks or the car stops running, many consumers have no choice but to finance a big-ticket purchase regardless of the rate environment.

Still, there are steps you can take to set yourself up to get the most competitive rate possible — even in a high-rate world. And some moves are smart to make no matter what the Fed is doing.

1. Pay down high-cost debt

Average credit card interest rates recently dipped below 20 percent for the first time since March 2023. But in practice, that milestone offers little relief. Someone carrying the average credit card balance ($6,473, per TransUnion) is saving only about $5 a month compared to when rates hit a record high in August 2024.

Opening a balance transfer card with a 0 percent introductory annual percentage rate (APR) would help you make a bigger dent if you can pay off the balance before the promotional period ends. If you owe a larger balance, you might have better luck working with a nonprofit credit counseling agency to negotiate lower rates and payments.

2. Compare offers from lenders, and keep your credit score in tip-top shape

If you know you’ll need to borrow this year, never take the first offer you see. Compare offers from at least three lenders before locking in a loan, and shop around for the most competitive rate. Borrowers with the strongest credit scores typically secure the best terms.

Keep your credit in good shape by paying your bills on time and using no more than 30 percent of your available credit.

3. Worried about the economy and the Fed? Build up a ‘rainy day’ fund

There are risks on both sides for the Fed. Lowering rates to help the job market could juice up inflation. Keeping rates too high for too long raises the risk of a recession. One thing that can help you feel more confident in your ability to weather uncertainty is an emergency fund.

Financial planners recommend keeping at least six months of essential expenses in savings, but don’t feel like you have to save it all at once. Start small by cutting back on discretionary spending — items like streaming subscriptions, takeout and impulse buys — and redirecting that freed-up cash to your emergency fund. Remember: Every little bit helps and is a step in the right direction.

Higher inflation also means money stored in a checking account or traditional brick-and-mortar bank could lose even more value. High-yield savings accounts are still offering returns outpacing the current inflation rate, helping you hang onto your purchasing power and grow your emergency fund even faster.

Any of these strategies can help you feel more in control of your finances, no matter what economic scenario unfolds.

“Usually, the labor market tips after the economy has already tipped,” Tilley says. “If we’re seeing the labor market slow and maybe move into negative right now, that’s a signal to macroeconomists the economy may have peaked like four months ago.”

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Fed holds interest rates steady, resisting pressure from Trump