Identity-theft victims pay a high price when their data get stolen

In 1999, Martina Henry pulled her credit report, only to discover a few unfamiliar credit cards had been taken out in her name. She reported the fraud to the credit bureaus, the creditors and ultimately her local police department.

“I thought (the situation) would be resolved quickly,” she says. Instead, 16 years later, the 57-year-old New York City resident is still struggling to have 11 fraudulent accounts — and the thousands of dollars owed on those accounts — removed from her credit reports.

Henry says these outstanding loans — three Capital One credit cards, six Chase credit cards, a U.S. Bank credit card and a Raymour & Flanigan Furniture credit card issued through Wells Fargo — have severely damaged her credit score. As a result, she has been unable to secure a mortgage, auto loan, credit card or even a department store line of credit.

“I have had to pay everything in cash,” Henry says. She’s also had to make court appearances, since a few of the creditors filed lawsuits against her to collect on the outstanding debts.

These cases were dismissed once the courts found there was no evidence to suggest Henry had actually opened any of the cards, but the creditors still refused to remove the accounts from her credit reports.

Feeling there was no other recourse, in April she filed her own lawsuit against the three credit bureaus, two debt collection companies (LVNV Funding LLC and Second Round LP) and the four banks. Henry is seeking punitive damages and hoping to finally get the accounts off of her credit report.

“I just want to get my credit report cleaned up,” in order to secure financing and move on with life, she says. “I could apply for a loan for a home, (and) maybe a credit card or two.”

Billions stolen from consumers annually

Henry’s story illustrates the potentially nightmarish consequences associated with identity theft — when a third party uses your personal information (name, address, Social Security number, driver’s license, insurance plan number or financial account number) to commit fraud in your name.

She’s one of many victims. According to a recent study from Javelin Strategy & Research, fraudsters stole $16 billion from 12.7 million U.S. consumers in 2014, with a new identity fraud victim popping up about every two seconds.

Not every identity theft case is as disruptive as Henry’s has been. For instance, Damani Goodson, 41, had little trouble getting the charges reversed after someone used the money in his bank account to fund a trip to Romania in 2001.

“I had to present … three forms of ID and I had to write my signature five times and I had to send that in to the bank,” says Goodson of Plainfield, New Jersey. “About a week later, they reversed the charges.”

Goodson also was able to get unfamiliar addresses removed from his credit report with relative ease.

“I had to keep checking, checking and checking to make sure it was removed, and ultimately it was,” he says.

Fallout from identity theft

These disparate experiences are the norm, given the many different ways a person’s identity can be compromised.

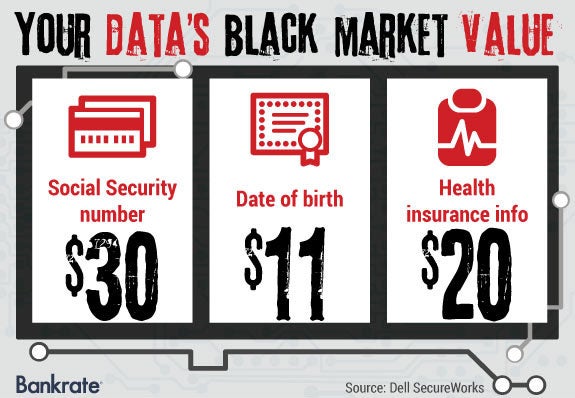

Scammers today buy and sell everything from debit card numbers that can be used for shopping sprees to Social Security numbers that can be used to take out new loans or secure employment. TurboTax temporarily halted e-filings this year over concerns that crooks had used the popular tax preparation software to commit tax fraud.

More often than not, the source of the fraud is unknown. Henry, for instance, is unsure how thieves obtained her personal information. She suspects someone stole a piece of mail that contained enough personal information to allow for the ID theft.

“We had a cluster of boxes outside, and my mail would go to other people’s boxes,” she says.

Generally, the more sensitive the information that thieves obtain, the worse the consequences can be for the consumer. For instance, simple credit card fraud is much easier to resolve than a laundry list of fraudulent claims attributed to your medical insurance information.

“You do have people where they have an existing account and they can resolve the issue by going to one merchant,” says Eva Velasquez, president and CEO of the Identity Theft Resource Center, a San Diego nonprofit organization that specializes in helping fraud victims resolve their cases. But “we hear on a regular basis from people in our call center who are definitely experiencing the type of ID theft that has a lot of complexity involved.”

In recent years, for example, the Identity Theft Resource Center has helped consumers who undeservedly ran afoul of the law after thieves wrote bad checks in their names. One client nearly lost his home after someone used his personal information to take out a mortgage.

At the Identity Theft Council, another group that aids fraud victims, a woman recently sought help after she faced arrest for two DUIs committed by someone who stole her driver’s license number, says Neal O’Farrell, executive director of the Walnut Creek, California-based organization.

“She may be facing months or even years of effort to get the matter cleared up and her record expunged,” O’Farrell says, because when it comes to these types of cases, “law enforcement has no process in place to disconnect you from the thief.”

Dispute process is complex

Getting well-versed on how the law seeks to protect you can be tricky. Laws vary by state, and different regulations get triggered depending on what type of information is involved, Velasquez says. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, for instance, provides federal protections for medical data and medical records.

Henry’s lawsuit cites violations of two other federal laws: the Fair Credit Reporting Act, or FCRA, which regulates how credit reporting agencies use your personal information, and the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, or FDCPA, which, among other things, allows you to dispute a debt someone is trying to get you to pay.

These “laws are very good,” says Gary Nitzkin, an attorney with Michigan Consumer Credit Lawyers near Detroit. They “don’t need to be changed” so much as the financial institutions need to do a better job of following them.

Consumer advocates have long argued that the credit reporting dispute process is overly complex and structured in a way that can benefit the businesses over the consumer.

“The (credit reporting agencies) are the platform, the merchants are the ones providing the data, the victims are the ones who the data is about,” Velasquez says, noting that victims have “the least amount of control over the data that is in the file, out of all the participants.”

The current structure has clearly irked consumers. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s complaint database, which began including public narratives this summer, is littered with grievances regarding the credit report dispute process. And, just this February, the agency said it planned to push for changes in this area as part of its credit score initiative.

‘Security … is a top priority’

Capital One, Chase, U.S. Bank, Experian, TransUnion and the Consumer Data Industry Association, which represents the three credit bureaus, all declined to comment on Henry’s case, citing the pending litigation. Equifax, LVNV Funding and Second Round did not respond to requests for comment.

Natalie Brown, vice president of consumer lending communications for Wells Fargo, said the bank was reviewing Henry’s complaint.

“The security of our customers’ information is a top priority,” she said in a written statement. “As a regular course of business, we monitor accounts for unusual patterns and activity and encourage our customers to do the same. In cases where a customer suspects fraud or identity theft, we ask them to notify us right away and provide tips on WellsFargo.com for other actions they should take to safeguard their accounts and personal information.”

How to better protect consumers

Doug Johnson, senior vice president of payments and cybersecurity policy at the American Bankers Association, says stories like Henry’s are outside the norm.

“No financial institution wants the customer to be victimized,” he says, citing recent changes that credit reporting agencies agreed to make to their dispute process.

Many of these changes were the result of a settlement the credit bureaus struck with 31 state attorneys general in May.

That agreement, among other things, requires the bureaus to provide a link to their online dispute websites on AnnualCreditReport.com; implement an escalated process for handling complicated disputes, including those that involve identity theft; and tell consumers how they can further dispute the outcome of an investigation.

“We’re working in the right direction,” Johnson says. “It’s not an easy thing in a large corporation to do that, but it’s not in the financial institution’s best interest to let those loans languish or take debt collection (action on them).”

Advocates say the new rules should prove helpful, but more may need to be done to mitigate the consequences associated with serious fraud.

“Until we fundamentally alter the process to allow for more consumer control issues … (problems) will continue to present themselves,” Velasquez says.

Ultimately, federal agencies may need to look beyond simply addressing credit reporting issues.

Right now “there’s no universal kill switch” that can prevent ID theft scenarios from escalating, Identity Theft Council’s O’Farrell says. “I think we need to be looking at something like a national identity theft registry.”

More theft on the way?

Improvements to the system would benefit all parties since there’s reason to believe identity theft will flourish.

The Federal Trade Commission, for instance, saw the number of identity theft complaints it received last year rise nearly 15% compared with 2013, to 332,646 complaints. (Identity theft was its biggest complaint category last year, making up 13% of overall complaints. Debt collection, at 11%, was second.)

Moreover, the horror stories could easily become more commonplace, thanks, at least in part, to technological advancements.

“There’s so much stolen information out there,” O’Farrell says, citing the recent spate of increasingly massive data breaches. “The thieves now have the tools to piece it all together.”

Passports for sale on an underground hacker market.

In fact, Javelin predicts there will be a growing interest in Social Security numbers over the next few years.

“This demand is what motivates the efforts of cybercriminals to compromise certain systems over others,” says Al Pascual, Javelin’s director of security and fraud. “Consumers could be affected by a variety of identity fraud schemes for a substantial number of years, should their SSNs be compromised.”

For now, though, even small breaches can cause big hassles.

Cynthia Fabian, a 57-year-old resident of Venice, Florida, closed all of her financial accounts after scammers ran up around $800 in charges with her business debit card. Fearing the hackers had access to her other personal information, she also elected to put a freeze on her credit reports.

“It’s a pain in the neck,” Fabian says. “You can’t just walk into a store and just apply for a charge card. You have to call the three (credit bureaus). You have to write a letter … but from what you get from it — no one can access your credit — it’s worth it. It’s what we have to do in this day and age.”

Protecting yourself

Unfortunately, given how prevalent data collection has become in our society, there’s no surefire way – short of going off the grid — to prevent identity theft.

You can, however, minimize the odds of it happening to you by limiting the number of third parties you share information with, frequently changing PINs and passwords to personal accounts, shopping only on encrypted websites and not clicking on links in emails from unknown sources, among other things.

To mitigate the potential consequences, should ID theft occur, regularly monitor financial accounts. More importantly, frequently check your credit report because mysterious line items, like new loans you didn’t apply for or even inaccurate addresses, will let you know that something is amiss.

“Early detection and resolution (are) key if you want to stop (thieves) from doing great amounts of damage,” Velasquez of the Identity Theft Resource Center says.

Here’s what to do if you spot illegal activity:

- Contact your creditors. Verify that there were, in fact, accounts opened up in your name. Ask to close or freeze them so no one can run up new charges in your name. “Recognize that the financial institution can be viewed as a partner,” the ABA’s Johnson says.

- Place a fraud alert on your credit reports. That way, you’ll be notified if someone tries to open a new account in your name. Per the FTC’s identity theft website, if you contact one bureau about a fraud alert, it’s required to contact the other two. Check all three versions of your credit report to make sure you understand the scope of the fraud. (Some lenders may not report to all three.)

- Register a complaint with the FTC. It won’t necessarily fix your issues, but the affidavit “can be one more tool that the consumer can use to show they are a victim,” Velasquez says. You can also file a complaint with the FBI.

- File a police report. It may be a hassle, but you’ll need one in order to have some of the federal protections kick in, Velasquez says. Police reports are often instrumental in getting disputes with the credit bureaus resolved. Take a copy of your FTC affidavit, a government-issued photo ID, proof of address and any other evidence you have to aid the process and show that the identity theft occurred. The FTC also suggests showing law enforcement this memo if they are reluctant to fill out a report for you. “Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” Nitzkin, the Michigan attorney, says.

- Formally dispute the accounts with all three credit bureaus. This will trigger your rights under the Fair Credit Reporting Act and the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. Once you formally file a dispute, bureaus have five days to notify the creditor, Nitzkin says. Both parties then have “30 days to conduct a reasonable re-investigation” into the account, he says.

- Consider a credit freeze. Especially if your Social Security number has been compromised, O’Farrell says. The freeze will prevent fraudsters from taking out more illegal loans in your name.

- Refrain from paying down any fraudulent debts. You may feel inclined to do so, given missed payments will wreak havoc on your credit score. However, putting dollars toward those debts can be viewed as admission that the loans belong to you, Nitzkin says, which can make getting them off your credit report that much harder.

Again, be sure to take these steps immediately. The sooner you report the fraud, “the easier it is to remedy,” Nitzkin says. “The law does not favor people sitting on their hands.”

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.